How To Read A Book

I thought I knew how to read books, but I was wrong.

My mental model of reading looked something like this:

The words go from the page, to your brain, and now you have knowledge. The author is lecturing and you are listening to all of this great information and getting smarter.

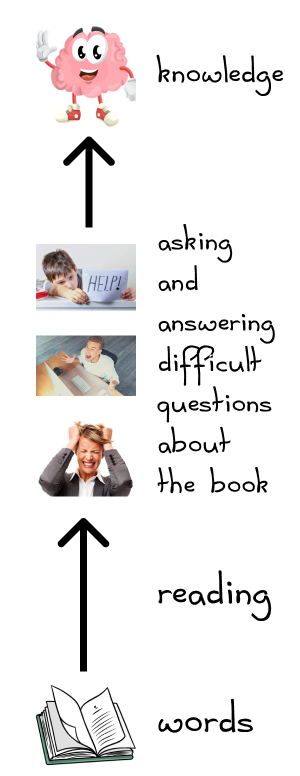

I’ve recently learned that’s not how things work. If you really want to gain something from reading a book, it should look more like this:

To gain true knowledge and understanding from the book, you have to go to work on it. You and the author need to have a conversation, and it’s up to you to figure out what’s true in the end.

Reading a lot of books doesn’t make you a good reader. Two people can read the same book, and one of them can gain a totally new understanding of the world, while the other learns a few points they can regurgitate in conversations.

To be fair, you may be reading for entertainment, and in that case you should have fun. You may be reading for information, as is the case with the news, and in that case you just need to get facts from the page into your head.

In this post, I’m talking about reading for understanding and insight, and specifically non-fiction books. A good book can improve your mental model of the world, increase your overall knowledge, and change the way you operate. But reading for understanding requires you to put in more effort than the other kinds of reading.

The first part of this post are the high level ideas behind this style of reading, which comes from the book “How To Read A Book”.

The second part of this post is a practical system I came up with to implement the ideas of this book. If you don’t care about theory, and just want to know what to do, skip to the second part.

Theory

Levels of reading

Elementary reading is being able to translate symbols on a page into meaningful chunks of information in your head. You already know how to do this, otherwise this would look like gibberish to you. For languages you don’t know, you are below the level of elementary reading.

Inspectional reading is a light and fast reading of a book which gives you an idea of what the book is generally about. It is useful for deciding whether or not to read a book, preparing for a book you are going to read more deeply, and dealing with very difficult books that are beyond your level.

Analytical reading is an in-depth reading for understanding and insight.

Syntopical reading is connecting multiple books that present various views on the same subject.

In general you’ll spend most of your time doing Analytical and Inspectional reading, so that’s what I’m going to focus on in this post.

Inspectional Reading

Inspectional reading is all about trying to get value from a book in a limited amount of time. There are two types of inspectional reading.

Pre-reading is something you’ll want to do on every book you read. It helps you decide whether or not to read the book in the first place by giving you a general idea of what to expect. 99% of books are not worth reading in-depth, so this is a useful ability.

If you’ve already decided that a book is worth reading analytically, pre-reading will give you insight into the structure and style of the book, which will increase your understanding.

Superficial reading is a tool for reading hard books that you’re scared to touch. What counts as a hard book is subjective to you and your level of reading, but classics like Critique of Pure Reason and The Wealth of Nations will probably sound hard to most people. Old classics are harder to read, so most people don’t read them. This is unfortunate since these are the books most worth reading, because they’ve stood the test of time.

Thankfully there is a hack to reading these books. To read superficially, you simply read through the book without stopping on things you don’t understand. If you see words you don’t understand, carry on until you find some you do understand. If a passage sounds like complete gibberish, carry on until you find a passage that makes sense.

In the end you might only understand 50% of the book, but now you have the right context needed to do an in-depth reading and understand the rest of it. Even if you never go back to do a more in-depth reading, understanding 50% of a hard book is much better than knowing nothing about it. (Note: This does not imply that understanding parts of a book means you fully understand the author’s arguments. You should definitely not have some false confidence that you truly know the book. You do, however, know more of what the book is about than most people.)

Analytical Reading

Analytical reading is reading for understanding and insight. The process of analytical reading can be summarized by four questions that you need to get the answer to for any book you read.

The Questions

- What is the book about at a high level?

- What specifically is the author saying?

- Is the book completely true, partially true, or not true at all?

- What now?

To get the answers to these questions, we have 15 rules of analytical reading to guide us.

Rules for finding out what a book is about

Classify the book according to kind and subject matter

You’ll be able to read a book better if you understand what kind of book you’re reading. We can classify non-fiction books broadly into two kinds: theoretical and practical.

Practical books are geared towards getting something done in the real world. An instruction guide on how to read a book is practical, as is an economics book about how to build the perfect economic system.

Theoretical books are more about ideas and concepts. A theoretical economics book might talk about whether it is even possible, in theory, to create a perfect economic system.

State what the whole book is about briefly

Write a few sentences representing the general idea of the book.

Enumerate its major parts in their order and relation, and outline these parts as you have outlined the whole

Break down the book’s structure, identify the parts of it, and state what each part is about. Then break each part down into sub-parts and repeat the process. You can do this to an infinite depth, so you’ll have to decide when to stop based on how complicated the book is, and how in-depth you want to read it.

Define the problem or problems the author has tried to solve

Every book represents an author’s attempt at solving one or more problems. Those can be theoretical problems like the extent of human knowledge, or practical problems like how to save the world. You need to know what problems the author is trying to solve in order to identify the important propositions and arguments.

Rules for interpreting a book’s contents

Come to terms with the author by interpreting his key words

A word or phrase can have many different meanings. A term is a specific meaning of a word or phrase.

The word “blog” can refer to a website where someone posts their personal life experiences, or a big media publication that writes long-form essays, or an email newsletter.

If I write an article titled “How to make a great blog”, you’d expect different advice if I was talking about making a large media publication vs a personal travel blog. As a reader, your job is to figure out from my use of the world “blog” exactly what I mean by that. If the meaning of “blog” you understand, and the meaning of “blog” I intended are the same, we have come to terms, and can have a productive conversation.

It is worth stressing the importance of this point because I think many arguments and disagreements are a result of people not coming to terms with each other. If two people are arguing about immigration, and one of them is referring to the immigration of skilled labor, while the other is referring to people illegally crossing a border, a meaningful discussion cannot take place. These people can only talk past each other, and leave the conversation having gained nothing.

Grasp the author’s leading propositions by dealing with their most important sentences

A proposition is an assertion about something. “Everyone should start a blog” is a proposition. It is a declaration that the author believes something, or doesn’t believe something. Of course, without any actual reasoning, the proposition is merely an unjustified opinion. This leads us to the next rule.

Know the author’s arguments, by finding them in, or constructing them out of, sequences of sentences

Unless someone is writing random thoughts, they probably have arguments for their propositions. You need to find those arguments, which may all be in the same paragraph, or may be in sentences spread out across different paragraphs. In order to determine if the author’s propositions are true, you need to find these arguments so you can assess them.

Determine which of their problems the author has solved, and which they have not; and of the latter, decide which the author knew they had failed to solve

In the beginning, you identified what problems the author was trying to solve. Once you finish reading the book, you can determine if the author solved these problems, if they created new problems along the way, and if they were aware of the problems they didn’t solve.

Rules for criticizing a book

General maxims of intellectual etiquette

Do not begin criticism until you have completed your outline and your interpretation of the book (Do not say you agree, disagree, or suspend judgment, until you can say “I understand”)

If you don’t understand something, then you can’t reasonably judge it.

Do not disagree disputatiously or contentiously

Don’t argue for no reason.

Demonstrate that you recognize the difference between knowledge and mere personal opinion by presenting good reasons for any critical judgment you make

“This book sucks because it’s stupid” isn’t good enough. Make a real argument.

Special criteria for points of criticism

Show where the author is unformed

The author is uninformed if they don’t have knowledge of something important. This happens a lot in history books, where people who wrote older history books didn’t have as much information as we do now. The book may be missing things because the author lacked the relevant knowledge.

Show where the author is misinformed

An author is misinformed if they have an incorrect notion of something. This is similar to being uninformed, but different because in this case they specifically hold an incorrect view of something and have made an assertion based on this factually incorrect information. For example, some older books may assume that the sun revolves around the earth, and use that as a basis for their arguments.

Show where the author is illogical

An author may be well-informed, but still use faulty logic in their arguments. For example: “Some people with blogs are rich and famous, therefore if you start a blog, you will become rich and famous.” It is true that some people with blogs are rich and famous, but it does not logically follow that I will definitely become rich and famous if I start a blog (still, a man can dream).

Show where the author’s analysis or account is incomplete

If the author is neither uninformed, misinformed, or illogical, you effectively agree with them. But even if you agree with what they wrote, it is possible that they didn’t fully solve the problems they were trying to. The book may be incomplete in some way.

You may agree with this article, but find it lacking when trying to read a history book. I didn’t address how to approach specific types of non-fiction books, so my article is incomplete in that regard.

Practical

In order to make all of this theory useful, we have to turn it into some kind of practical system. Here is one system for implementing better reading. (This is a work in progress. I’ll update this post as my system changes.)

Before diving into this, it is worth noting that this whole system may seem like a ton of work. It represents the most in-depth reading that can be done. In reality, you should vary how much of this stuff you do based on how important you think the book is.

“Some books are to be tasted, others to be swallowed, and some few to be chewed and digested; that is, some books are to be read only in parts; others to be read, but not curiously; and some few are to be read wholly, and with diligence and attention.” - Francis Bacon

Pre-reading

Always do a pre-reading before doing analytical reading.

You probably already have some intuition about how to skim a book, and there are no hard rules, but here are some suggestions on how to pre-read a book:

- Look at the title page and the preface

- Study the table of contents to obtain a general sense of the book’s structure

- Check the index

- Read the publisher’s blurb

- Look at the chapters that seem to be pivotal to the main argument of the book

- Turn the pages, dipping in here and there, reading a paragraph or two, sometimes several pages in a sequence, never more than that.

One other thing I’ve found helpful is listening to an interview with the author where they talk about the book. This is one of the easiest ways to figure out the main problem the book is trying to solve, and the main propositions and arguments.

The Template

The first part of the system is a notetaking template that you’ll fill out as you read the book. You should be able to fill out some parts of it after your pre-reading.

Book Title:

Author:

Goodreads Link:

Kind of book: (practical or theoretical)

Subject: (mathematics, philosophy, science, economics, etc.)

What the book is about

(This should only be a few sentences long)

What problem(s) is the author trying to solve?

- Problem 1

- Did they solve it by the end? Did they create any new problems while trying to solve it?

- Yes/No

- If no: Did they know they failed to solve it?

- Newly Created Unsolved Problem 1

- Did they know they failed to solve it?

- Yes/No

- Did they solve it by the end? Did they create any new problems while trying to solve it?

- Problem 2

Outline

(Outline the structure of the book by copying the table of contents if there is one. If there isn’t a good table of contents, you’ll have to do a bit more work to figure out the sections of the book. Do this after your pre-reading. You can take notes within this structure as you read chapters of the book. Write a brief summary of each chapter when you finish it.)

- Chapter 1

- Brief summary

- Chapter 2

Summary

(Prove that you understand what the book is saying by writing a summary of it in your own words.)

Criticism

(The criticism is effectively a review of the book. Criticism can be positive.)

Review the rules for good criticism:

- Do not begin criticism until you have completed your outline and your interpretation of the book (Do not say you agree, disagree, or suspend judgment, until you can say “I understand”)

- If you don’t understand something, then you can’t reasonably judge it.

- Do not disagree disputatiously or contentiously.

- Don’t argue for no reason.

- Demonstrate that you recognize the difference between knowledge and mere personal opinion by presenting good reasons for any critical judgment you make.

- “This book sucks because it’s stupid” isn’t good enough. Make a real argument.

Points where the author is uninformed

Points where the author is misinformed

Points where the author is illogical

Points where the author’s analysis is incomplete

Conclusion

If you have found no points where the author is uninformed, misinformed, or illogical, then you must agree with them.

However, even if you agree with them, they might not have fully solved all of their problems. They may have failed to mention important things, or the work might be otherwise lacking in some way. In this case, you should note the limitations of the work.

In the end you can either agree, disagree, or suspend judgment on the whole (i.e you may agree with what is written, but the author’s analysis is too incomplete, so you cannot truly judge it.)

While You Read

I read using the kindle app on desktop, so this system will be specific to that, but you can easily adapt it to whatever you use.

This is all going to sound very intense, so let me make this clear again: you don’t have to do every single one of these things for every book you read. Some books are important to you and you’ll want to go hard on them. For others you might barely do any of this. That’s fine, and that’s how it should be.

When you see a key word appear for the first time, highlight it in blue and add a note explaining what the author means by it (the term). If that same key word appears somewhere else with a different meaning, then do the same thing. Otherwise, if it refers to the same term, no action is needed.

When you identify an important proposition, highlight it in red.

When you identify a sequence of sentences that make an argument for a given proposition, add a note to the start of each relevant sentence that makes up the argument, indicating its number in the sequence (i.e 1, 2, 3). When adding the note to the first sentence in the sequence, also state the proposition that the argument is for. (e.g “1. Minimum wage needs to be increased” where 1 means it is the first sentence in the argument, and the proposition is that minimum wage needs to be increased)

When you read something that you want to respond to, or have thoughts on, have a conversation with the author by adding a note to the relevant passage. (kindle will automatically highlight these in yellow)

If you have general thoughts that are not specific to any particular passage, leave a note on the first word on the page (kindle will not highlight anything).

If something stands out to you as interesting or important, but you don’t have any comment on it, highlight it in orange.

Now when you’re going through the book again, you know that:

- Blue highlights means a key word is appearing as a new term (i.e with a new meaning) for the first time.

- Red highlights are important propositions made by the author.

- Yellow highlights are your thoughts and questions on specific passages. They represent your conversation with the author.

- Orange highlights are things that stood out to you.

- Numerical notes (possibly with no highlights) are sentences that are part of important arguments.

- The first word on a page may have a note with general thoughts that are not related to a specific passage.

Conclusion

We all suck at reading, but it is possible to suck less. The more work you’re willing to put into reading, the more you’re going to get out of the book. Some books just need to be tasted, while others should be chewed and digested.

Hopefully this system can help you in your journey to read better. If you have any thoughts on how to improve it, let me know.

“For those of us who are not in school…our continuing education depends mainly on books alone, read without a teacher’s help. Therefore if we are disposed to go on learning and discovering, we must know how to make books teach us well.” - Mortimer J. Adler and Charles Van Doren (How To Read A Book, p. 15)

(This post was based on “How To Read A Book”, and if you thought these ideas were interesting, you should definitely read it, as it goes a lot more in-depth than I did here.)